For any American sports fan with a pulse, the afternoon of Saturday, July 10, 1999, brought a moment for the ages. The U.S. and China battled to a draw in the Women’s World Cup final, culminating in a tense penalty-kick shootout. A Rose Bowl crowd of 91,000, and another 13 million across the country, attentively watched. In the shootout’s third round, American goalie Briana Scurry made a stadium-shaking block on Liu Ying. Minutes later, Brandi Chastain delivered the game-clinching goal, then delivered an iconic image as she ripped off her jersey in celebration.

The next day, in the rolling hills of northeastern France, cyclist Lance Armstrong offered his own bit of American triumph. Draped in a blue United States Postal Service kit, topped with a blue aerodynamic helmet, Armstrong tore through a 56-kilometer time trial that began and ended in the ancient city of Metz. In doing so, he took the overall lead in the Tour de France, peeling off his own jersey in favor of the leader’s yellow.

That weekend marked the climax of what might be dubbed The Summer of Swagger: a closing of the century with American athletic victory on the global stage, and a particular brand of sports nationalism that both reflected the past and foretold the future. It was situated between the Cold War and the War on Terrorism, a period in which American identity was not so clearly defined against enemies abroad. As such, athletic victory did not carry quite the same weight of nationalist-militarist symbolism. However, this period was to be brief, and the events of 1999 foretold some of the major players to come: women’s soccer (and women’s national teams generally), Lance Armstrong, and Serena Williams, who won her first major tournament at the U.S. Open in September.

Two decades later, it’s easy to look back on that era as the “end of innocence,” even if innocence is nothing more than a myth. Yet it was also an era of prescience, on athletic fields and beyond, meriting a glance backward.

The Summer in Stages

Writing for the Daily Beast, Nathan Webster describes it as “our last innocent, giddy summer,” a time when “we didn’t know it may never be that good again.” His is a typically nostalgic, generalizing take made through rose-colored glasses. Yet Webster does also recognize that “summer 1999 was full of portent.” Napster signaled the digital-sharing of music and other media forms, soon to upend the culture industry. Star Wars: The Phantom Menace kicked off a movie sequel revival that has continued ever since. Silicon Valley investors enjoyed a dot-com bubble that would be short-lived yet foreshadow other Valley bubbles. And Osama Bin Laden was added to the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

Amid these events, American athletes made their own pop-culture impact on the international stage. First up was the Women’s National Soccer Team, who from mid-June to mid-July emerged as the team of the summer. This was the first generation of female athletes who had grown up with Title IX, embracing sports participation and excellence as part of women’s “physical liberation.” And in the 1990s, U.S. women’s soccer had gained a face in Mia Hamm. She was the most famous player in the world, breaking offensive records while achieving the kind of pop-culture visibility usually denied to female team-sport athletes. Hamm was joined on the national team by accomplished veterans in Brandi Chastain, Briana Scurry, Julie Foudy, and international star Michelle Akers.

Playing elimination games in D.C., Palo Alto, and Pasadena, the team gathered a loyal national following from coast to coast. It was by no means an easy path to the World Cup trophy. A 3-2 victory over Germany in the quarterfinals was followed by a two-goal win over Brazil. In the final, the U.S. needed a late header save from Kristin Lilley, standing at the goal line, to reach the final shootout. Yet when Chastain knocked the Americans’ fifth penalty kick into the net, she etched their place in history. Sports Illustrated, known for an annual issue featuring scantily clad models in bikinis, published a cover image of a female athlete, in athletic shorts and sports bra, flexing her arms in triumph. In December, they named the team Sportswomen of the Year.

Across the Atlantic, another American athlete was crafting his own legacy. Lance Armstrong had endured a very public episode of cancer diagnosis and treatment, not only surviving but returning to cycling’s highest level of competition. It was the perfect symbiosis of life-and-sports metaphor. Armstrong epitomized a fighter’s mentality from the hospital room to the road course. (This symbiosis made his story highly marketable.) Armstrong was also, as would prove ironic, a much-desired new star for the Tour de France, which in 1999 was dubbed the “Tour of Renewal” following a previous edition plagued by doping-related investigations, revelations, and rider protests.

After gaining the overall lead in the Metz time trial, Armstrong essentially locked up victory two days later with a furious ascent up the Sestrière mountain. Riding in a small group, Armstrong stood up on his pedals, upshifted, and suddenly broke away, a flash of yellow and blue as he climbed with seemingly little exertion. From that point, he protected his lead until arriving at the finish line in Paris on July 25.

By coincidence, I stood among the crowd on the Champs-Élysées that day, positioned close to the stage on which Armstrong celebrated his Tour victory. One distinct memory stands out: a group of young Americans, decked out in red, white, and blue, cheered and danced in celebration. Nearby, an older European man, perhaps French, simply cursed and threw his hat onto the ground. If this was made-for-TV, it sure felt like it.

Despite widespread desires for a “clean” race, Armstrong could not escape suspicion, especially after he tested positive for banned corticosteroids (and, it was later revealed, blood-boosting EPO). Yet Armstrong employed what would be a familiar strategy, meeting with a New York Times writer who helped propagate the narrative of a European press out to get the American intruder. The retaliation would prove to be effective. He began his ascent to icon status in the U.S., securing $7.5 million in post-race endorsement deals, promoting his Livestrong foundation, and eventually turning the yellow bracelet into an icon of its own.

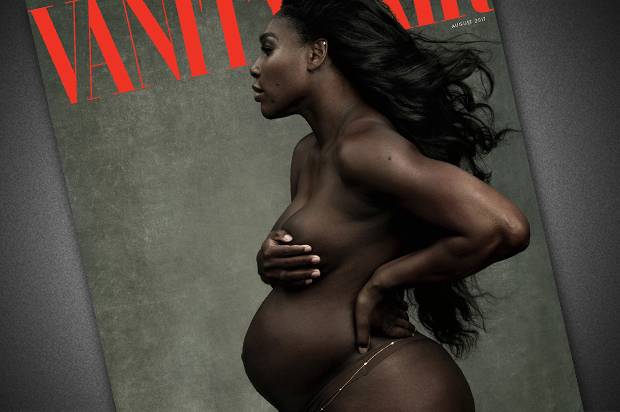

A few weeks later, one more American prepared to enter the global spotlight. Seventeen-year-old Serena Williams was best known as the sister of Venus, a tennis prodigy who had turned professional at the age of fourteen. The Williams sisters were, like Tiger Woods, inevitably conspicuous in a game long draped in whiteness, particularly given their penchant for wearing their hair in brightly beaded braids. Yet like Woods, they would also be conspicuous for their athletic greatness, and that statement was emphatically made at Flushing Meadows.

Like the U.S. women’s soccer team, Serena’s path to the championship was far from smooth. Facing all-time great Monica Seles in the quarterfinals, then the defending Open champion Lindsay Davenport in the semifinals, Williams won two out of three sets against each. Martina Hingis, the world number one who had just taken out Venus, waited in the final. Serena defeated her teenaged rival in straight sets, showcasing the screaming serves, forehands, and all-around mix of power and finesse for which she would become famous.

According to an account of the final, Williams “fielded a congratulatory call from President Clinton and his daughter, Chelsea. Williams said they talked tennis, not politics.” She added, “I’m not into politics.”

Williams won the final on September 11, 1999, about a dozen miles from lower Manhattan. Her victory did not resonate at the same level as the earlier American triumphs – after all, it competed with the nearby Yankees’ run to another World Series title – yet it would prove to be the most symbolically loaded. Two years later, the skyline changed, and for two decades afterward, Williams continues to dominate the game unlike any other player in the Open era. She would project the kind of sustained success that many Americans soon craved amid a renewal of instability.

The Legacies

Viewed in retrospect, the summer of ’99 featured a cast of sports figures whose impact would resonate over the next two decades. Inevitably, this resonance was shaped by the events of September 11, 2001, and the aftermath, particularly the injection of American nationalism into games at home and abroad. From football fields to baseball diamonds, patriot games largely demanded assent to War on Terror ideology. Yet it also bears noting that each athletic representative carved their own path and their own meanings. And in each case, they inevitably shed their “innocence” and engaged in social-political controversy.

The U.S. Women’s Soccer Team set a bar nearly impossible to match, and their failure to earn a spot in the 2003 or 2007 World Cup finals, along with a relative absence of compelling star power, proved disappointing. Also disappointing was the closure of two professional women’s soccer leagues in the U.S., a sign that Americans are generally interested in women’s sports only when imbued with nationalism and absent capable male counterparts. However, the 2010s revival has included a runners-up finish (2011), championship (2015), and a run to this year’s final on Sunday. It does seem that U.S. fans are now able to, pardon the predictable pun, party like it’s 1999.

Accompanying the revival have been actions that reflect the activist present. On International Women’s Day (March 8), a group of female players sued the U.S. Soccer Federation for fair wages relative to the men. It was a move that reflected long-simmering frustrations over pay inequality given the success, in both wins and ratings, of the women’s team. And in more recent weeks, veteran Megan Rapinoe (having already established leftist credentials) reaffirmed her disinterest in visiting the Trump White House, setting off an expected Twitterflurry from the President.

On the tennis court, Serena Williams would also enjoy the recognition afforded a woman playing alongside forgettable American men. She has won an Open era-record 23 major singles titles, including six U.S. Opens, along with over a dozen doubles titles. Along the way, Williams has exuded a brand of on-court ferocity that challenges notions of how a female tennis player can and should play the game.

And despite her adolescent intentions, Williams couldn’t avoid politics. She grew into the athletic embodiment of #blackgirlmagic, exuding unapologetic blackness in the forms of aesthetic style, curves, assertiveness, and all-around power. This stance inevitably drew backlash, a steady undercurrent punctuated by moments of candor, yet Williams persisted to represent black excellence in an athletic space where blackness remains far more the exception than the rule. (Deserving of its own discussion is Briana Scurry’s overlapping position.)

Finally, there is Armstrong. More than the others, he emerged as a nationalist symbol of post-9/11 American swagger, a man who joined the President, a fellow Texan, in taking on the world. As described by sports scholar Kyle Kusz, Armstrong was just one figure in the “reactionary form of White [male] cultural nationalism” that marked the larger War on Terror project.

He used this position to his public relations advantage. As Armstrong racked up Tour de France victories, seven in all, he was increasingly hounded by European journalists who suspected that he was enhancing performance as much as any other cyclist. In response, Armstrong appealed to “freedom fries”-eating Americans back home. He argued that, ever since 1999, these accusations were merely a product of European, particularly French, resentment of a Yankee beating them at their own sport.

It worked for a while. Yet after his former teammates turned against him, Armstrong finally confessed to having participated in cycling’s performance-enhancement culture. And with that, a turn-of-the-century American sports hero (somewhat like another, minus the redemption) experienced his sudden fall from grace. He was quickly dropped from the record books, endorsement deals, and his own foundation.

Armstrong’s fate, and others’ of 1999, reveals the ultimate fluidity and fragility of sports celebrity. He rode a wave of nationalism-buoyed invincibility, only to crash the hardest. The women’s soccer team experienced a decade-long hangover, only to rise again. And Williams, the quietest star of that summer, ultimately won the most of them all.

What we find, in retrospect, is a cautionary tale about what kinds of footprints are left in the sands of time. Three parties emerged in a similar time and place, poised to represent American sporting excellence in the decade ahead. None could have anticipated the social-political upheaval soon to come, and few others could have anticipated where each party’s path would take them. As we survey the present with a different kind of uncertainty, we can only guess, on playing fields, courts, and elsewhere, what lies ahead.