In the days leading up to the 2019 Masters golf tournament, a familiar buzz punctuated the air. Over a decade since he’d won his last major, now solidly middle-aged, Tiger Woods was still the featured player in the annual spectacle at Augusta National Golf Club. Even though Tiger wasn’t the favorite, or even in the top five, his image dominated the previews. It was a remarkable sign of his staying power as the face of the sport.

And on Sunday afternoon, the buzz turned into a roar. Woods chased down the leader in the final round (the first time he’d done so in a major) and, with a short putt on the 18th hole, added an improbable green jacket to his collection. The reactions said it all: he yelled with raised fists, and the crowd responded in kind. It was a display that reflected the sheer joy of the moment.

Why, then, did his victory generate such elation? The obvious answer lies on the surface. We are often captivated by the story of an icon’s rise, fall, and rise again, especially an athlete who first captured the nation’s attention as a child. There is also the nostalgia inherent to a comeback. Tiger in victorious Sunday red connected us to moments in the past that seemed destined to stay there. We could party like it’s 1999.

Yet there are deeper politics, right to the nation’s core, reflected in the response to Woods’ competitive redemption. To truly understand the meanings of his victories, from the first to most recent, we must dig into the changing political currents in which they played out.

After a twenty-year buildup, Tiger (born Eldrick) Woods exploded onto, and simply exploded, the professional golf scene in the mid ’90s. The event was quickly branded, with Nike converting his line “Hello, world” into one of their more iconic ads. Woods was so compelling because he represented, in somewhat literal terms, a fresh new face in the world of professional golf. Not only was he a generational phenom, but he also projected an identity unfamiliar to golf or, for that matter, most any other major American sports league.

Woods was, in his own description, “Cablinasian”: a blend of Caucasian (white), black, American Indian, and Asian ancestry. He embodied the new “faces of America,” captured on magazine covers at the time, whose racial hybridity (ambiguity) offered promise of a post-racial 21st century. In the aftermath of his first Masters victory in 1997, Oprah proclaimed him “America’s son.” Woods’ success, in a sport long defined by color and class lines, was the ultimate demonstration of an imagined nation in which multiculturalist meritocracy was, and would be, the norm.

Yet he was not elevated to this role merely for his ancestry and golf skills. Following the model set by Michael Jordan, Woods tended to avoid explicit commentary on race and inequality, instead focusing on his own competitive (and financial) success. This wasn’t always the case. As a fourteen-year-old, he specified that he was most interested in winning the tournament at Augusta National because of “The way blacks have been treated there. [Like] they shouldn’t be there. If I win that tournament, it will be really big for us.” By the time he turned pro, however, there was no “us.” Woods self-identified not as black but as multiethnic. The ambiguity allowed him to largely avoid the burden of representation.

Of course, this burden couldn’t be avoided altogether. His not-whiteness came to light when conjured by others: see player Fuzzy Zoeller’s and Golf Channel commentator Kelly Tilghman’s racially tinged remarks on Woods. Race was also difficult to ignore within the episode that effectively closed the first chapter of his career. In the weeks following that infamous Thanksgiving night, it was revealed that Woods had cheated on his white wife with a number of other white women. Some of the more salacious details played into long-standing stereotypes of black male hypersexuality.

And just two years ago, more troubles brought his identity to light once again. Woods was arrested for driving under the influence of drugs and alcohol. In the police report, he was listed not as multiethnic but as “black.” Woods attributed the incident to the painkillers he had been taking after a series of back surgeries.

The arrest appeared to be a consolidation of his ultimate failures: to stay healthy and win golf tournaments while maintaining a marketable, racially ambiguous identity. These failures symbolized, in some ways, the larger deterioration of the multiculturalist hope inspired by Woods two decades later. And in that context, his return would be all the more important.

This year’s edition of The Masters took place amid a backdrop of heightened political polarity. The campaign of Donald Trump brought such polarity into sharp focus, and in the aftermath of his election, according to a Pew Research Center study, “racial attitudes among white voters were the single most significant predictor of support for Trump’s performance six months into his presidency.” Racial-political division, while always central to the national fabric, was now foregrounded in a way that raised anxieties about a democracy in crisis.

Among other effects, the discourses of the 2010s have brought whiteness into the spotlight, with talk of white privilege, talk of white culture, and talk of white nationalism. It is harder than ever for white people to hide in plain sight, and the same goes for the white spaces they occupy.

One such space is, historically and presently, the Professional Golf Association (PGA) Tour. Last year, outgoing PGA CEO Pete Bevacqua acknowledged that, despite some growing diversity due to globalization (particularly the ascent of Asian players), there is still a long way to go in terms of attracting non-white Americans. As Bevacqua remarked, inadvertently echoing the language that surrounded Woods’ arrival decades earlier, the Tour “needs to look more like the face of America.”

Absent the numbers, Woods remains that face. And he continues to blend non-white identity with deference to white-identity politics. In the era of athlete activism, Woods is conspicuously silent on issues of race and social justice. He has also declined to criticize President Trump’s embrace of white nationalism or attacks on activist athletes. He commented this past August, “Well, he’s the President of the United States. You have to respect the office. No matter who is in the office, you may like, dislike personality or the politics, but we all must respect the office.” Given one more chance to comment on race, Woods gave his closing statement. “No. I just finished 72 holes, and I’m really hungry.”

With that dodge, Woods demonstrated that he was still the man for the moment: multiethnic, politically noncommittal, and laser-focused on making history by breaking more golf records. In an era in which multiculturalist optimism has become a defensive stance, Woods continues to embody its ideals without a word that might offend those greenside. And that is his ultimate gift to professional golf. He has returned to remind everyone that the links are as meritocratic as the rest of America, if you want to believe it hard enough.

Judging by the smiles of those around the 18th green on Sunday, it appears many people still do. Woods’ victory was the ultimate form of redemption. On a personal level, obviously, he captured a 15th major victory that once seemed out of reach even to himself. Yet the redemption went much further. Sure, beyond the pristine, manicured landscape of Augusta National lay a nation whose centuries-old fault lines had opened up in ways that were nearly impossible to ignore. But they could be ignored, even if for just a moment, in the ecstasy around a man who had been straddling those lines since he was old enough to walk.

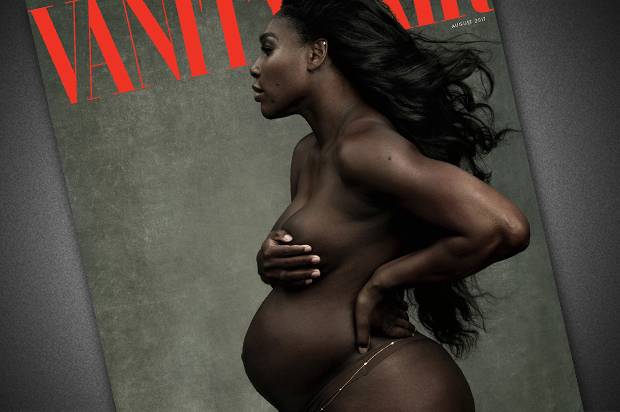

[…] a tennis prodigy who had turned professional at the age of fourteen. The Williams sisters were, like Tiger Woods, inevitably conspicuous in a game long draped in whiteness, particularly given their penchant for […]

[…] Tiger Woods and the Cycle of American Redemption. […]