“Is that a gun?” I ask, as I pull my hand back between the black, jail bars.

The Polish interpreter, Jakub, looks at me incredulously. “I do not know what he doscz.”

“Screw that. He can hand me the money. I’ll wait.”

I breathe slowly, and then quickly, and then slowly again, like I’m shooting a free throw for “game.” The stack of purple euro banknotes feels like a Venus flytrap situation. That’s a lot of money to me. That’s a lot of money to anyone who has never made a lot of money playing professional basketball.

Where the hell am I again?

The bright purple bills are brand new, and each one is worth 500 euros, and there are at least 20 of them. I try to remember what my agent had negotiated in the contract. “6,500 euros to be paid by the seventh of every month.” It was already the 14th. I glance over my shoulder to look at my coach. He is waiting impatiently, texting on his flip phone. He is genuinely disinterested in this entire process.

Is this a test? Do I need to do something?

“Do I need to say something? My name? Like what’s the problem here, Jakub?”

“I thinkcz he’s mess witcz youcz,” Jakub says, tilting his head towards me. He is standing too close to my face. I think I can smell a faint touch of coleslaw or something.

“What? Why? Also, how do I send cash home every month?”

“Western thez Union,” Andrzej Kowalczyk, my Polish EBL coach says as he turns and grins. His teeth are scummy, yellow-white Chiclets, and he is always wearing the same brown corduroy jacket and tight, light-stonewashed jeans. His portly cheeks are flushed red, and he is breathing too hard for texting, but then again, he is always smoking at halftime of our games, at our bus stops, before our games, the end of our games, and then again on the ride home from our games.

“Jest koszykówka MVP,” coach says to the man behind the black, one-inch bars.

“Youcz?”

“Me?”

“Yahh, youcz,” the appliance man says in broken English.

“Yah—me.”

This is an awkward agreement. The wispy-white-haired, appliance man slides the money forward slowly. I think my coach just told him that I was going to be MVP of the EBL, but I’m not entirely sure.

“Guuuud.”

I fold the bills and tuck the wad of crisp, purple euros into my spandex and walk into the darkness of a Polish city that I’ve been in for one week, trying to let go of the heavy suspicion that is hanging on me like the fall of communism.

——————————

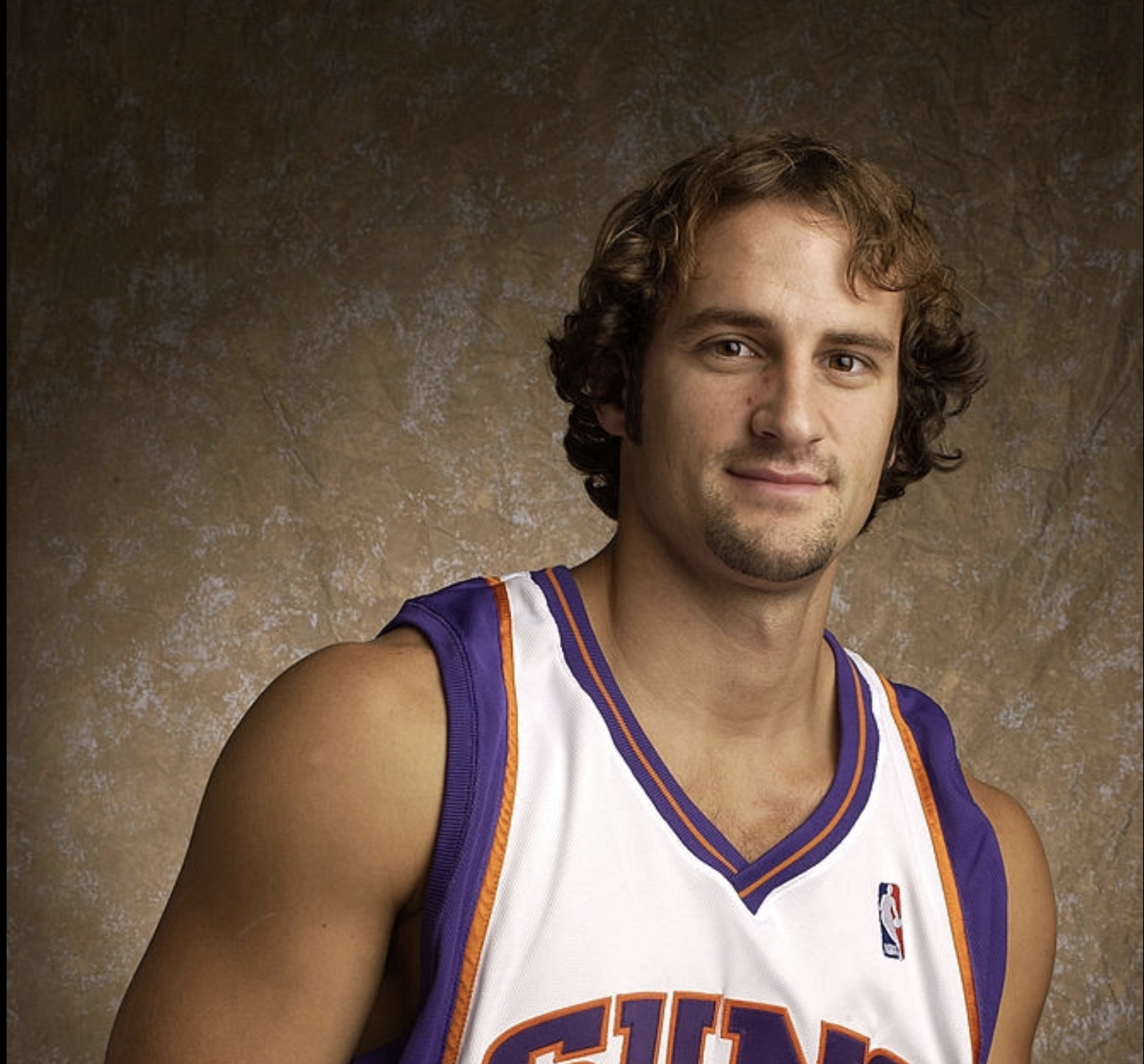

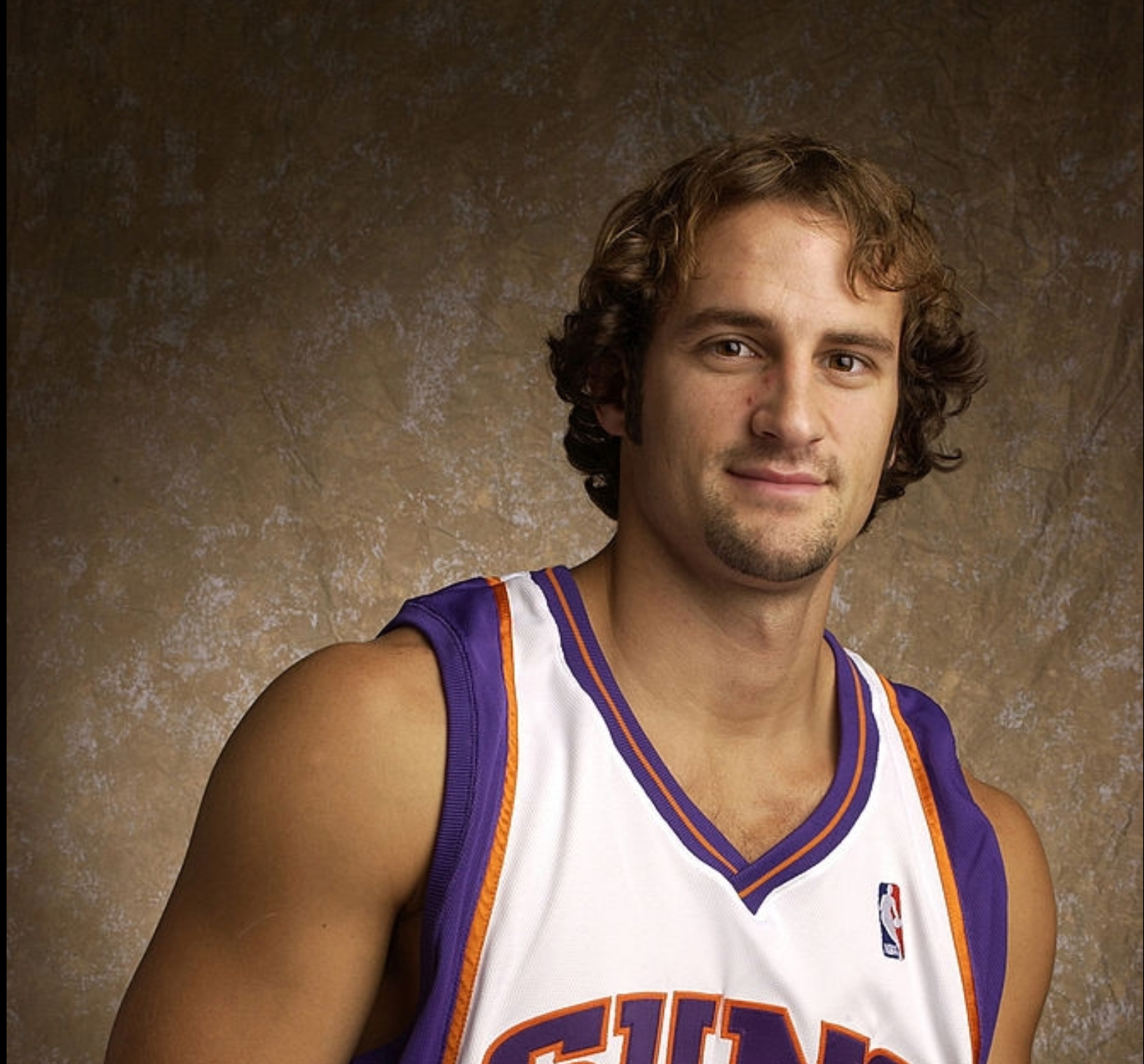

The first check I received in the NBA on a free agent rookie contract with the Phoenix Suns felt a little light. It was around three thousand dollars. I thought it was supposed to be like $5,000, but contracts in the NBA go by state tax laws, and they ask if you want to withhold taxes in escrow, so I must have said yes. In Europe, contracts are always paid in net, so you never know what the taxes are, or you get paid in cash under the table like in Poland.

In the NBA, I got paid by check for one week of basketball practice. It came in a whitish rectangle envelope with something like “Phoenix Suns LLC” on it. I photocopied it and have it next to my Kent State All-Time Leading Scorer basketball and trophy case that I keep locked away in my dad’s attic in plastic bins. It was a monumental moment for me back then.

My Boyhood Dream Realized…NBA ROOKIE FREE AGENT CONTRACT-PAID

Until seven seconds later, I got cut by the “7 Seconds or Less Suns,” and I thought, “Damn man, you got paid by an NBA team. How cool is that!” Not many guys get paid by an NBA team. I relished being an NBA free agent rookie for a few days, but then, Coach Johnson told me I was off the team. “Huffman, thank you for your services. We have to let you go.”

Getting the pink slip sucked the life out of me. It sunk in on the flight home, staring out a plane window at what should have been a beautiful pink-orange-Arizona-sunset knowing my life’s NBA dream was probably over and not one dollar of that three thousand could reconcile the pain of feeling like I still deserved a chance.

I had put all my eggs into the NBA basket, got cut, cracked, and bled out. The the only thing I can say is watch the scene with Artax in the NeverEnding Story as Atreyu is pulling his sinking horse through the Swamp of Sadness.

I was Artax—fuck it, man, just let me sink.

After the Phoenix Suns, I figured out the NBA guaranteed guys got paid on the first and the 15th of the month like clockwork. And I always wondered if the superstars that probably chose to not withhold state or federal taxes in escrow went bankrupt for it. Guys like Shawn Kemp ($91 million career earnings), Darius Miles ($61 million), Eddy Curry ($70 million), Antoine Walker ($108 million), and Allen Iverson ($154 million).

Graciously, I paid my Arizona state taxes, but who knows what I would have bought with that extra $7,000 if it had been in my account. And the thing about getting paid and playing in the NBA as a free agent is you can get cut at any time. Just like in Europe. Nothing is guaranteed unless you just get that cash wired like NBA OGs (Original Gangstas for you young folk). The OGs get paid, and then they spend it like Richard Pryor in Brewster’s Millions.

I can’t blame them.

Well, I guess I can. They were the reason I only got paid for one week of NBA free agent, rookie salary—because they were better than me at basketball.

In college, I got paid. It started off small. My mom was part of it. She would call me and say, “Honey, do you know what this paperwork is?”

I’d say, “What paperwork?”

“Oh, never mind. I’ll figure it out.”

“Sure, mom. Let me know,” I’d say, furiously hitting my keypad’s hotkeys while playing StarCraft II.

“Shit. Damn Zerglings.”

“What honey? Zerglaangs? Who’s that?”

“Oh, sorry mom. No. Nothing. Love you.”

“Love you.”

And then a month would go by and I’d get a ubiquitous looking check in the mail (at my trashy Franklin Street apartment) and cash it immediately. In college, that money was the best thing ever. I’d head to the mall and run towards Finish Line and go Darvin H.A.M. on basketball gear. Try on Jordans. Try on running shoes. Try on shorts. Try on Jordans again. Then I’d sprint down the mall to the other side and try on Foot Locker’s stuff. After hours of thoughtful deliberation, I’d finally always end up with the first pair I put on. A true baller always had on Jordans. Then I’d head back into practice to show them off.

“Huff, where’d you get those shoes man?” our small forward Demetric would ask me.

“Nowhere Shaw. Mind your business,” I’d say to him. He would be crooking his neck out of his locker like a crane on steroids.

“Those nice boy. Those real nice.”

I’d look over at Antonio Gates, who’d be smiling at me. Money changes your life in college. Most of my teammates came from nothing. I just came from a divorced household. Regardless, the money means you are worth something. The money is the reason you didn’t start playing, but it is the reason you’ve always wanted to play, because it represents the sports idols you’ve watched play as a kid. You’ve always wanted to be worthy of it, to get to the highest echelon of athletes and get paid, and more importantly, feel like the NBA superstars.

“Shaw… Tone… you touch these shoes, I’ll kill you.”

“Huff, you good boy. You good. I ain’t gonna touch them. And you ain’t gonna do nothing if I did.”

I shake my head. He’s probably right. Tone is a big boy.

Later that season, Shaw tried to throw a ball off the back of a Buffalo defender under our hoop on the road, and we lost our only Mid-American Conference game of the year by one point. We would have been undefeated if it weren’t for that dumbass play. Later that week, before we rattled off 22 wins in a row going to the Elite 8, we fought in the locker room and I threw my Jordan at his face and then tackled him. It was just another day in the life of Kent State Basketball.

My mom called me again later that night.

“Trevor?”

“Mom?”

“Did you get that Pell Grant check?”

“What’s that mom?”

“Honey, I saw you got new shoes on TV. You did get your first Pell check, didn’t you?”

“Wait. What? There’s more?”

I shut my computer and stopped playing StarCraft. This could wait.

“We’ll give you 130k in Euros with a signing bonus, plus a house on the beach, a car, and a chance at a championship.”

I sighed and looked outside. For the first time in my life, I felt disloyal. I thought back to my days playing in Poland. In Portugal. Making $50k teacher salaries, driving my beat-up, red 1980 Ford Pinto in Portugal (I called her “The Red Dragon” until she caught on fire and exploded on a drive to Porto). Luckily, I’m fast and got away before she killed me. There was the fake Polish checks (I should have only trusted the appliance man) and getting run out of cities because I lost or played poorly.

I thought about the money the Oostende, Belgian GM was offering. I knew he was high up in politics in Belgium. He was no pawn. Maybe I could get my Belgian citizenship and not be counted as an American player. I’d get paid double. And there was no middle man. No broker. No commissions. Did he always negotiate like this?

Then I thought about getting paid in Venezuela, how the GM there, in Caracas, had 12 bodyguards and his 12-year-old kids were hanging on me in the locker room before games.

“Trevoooor. You play muy bien.”

“Gracias.”

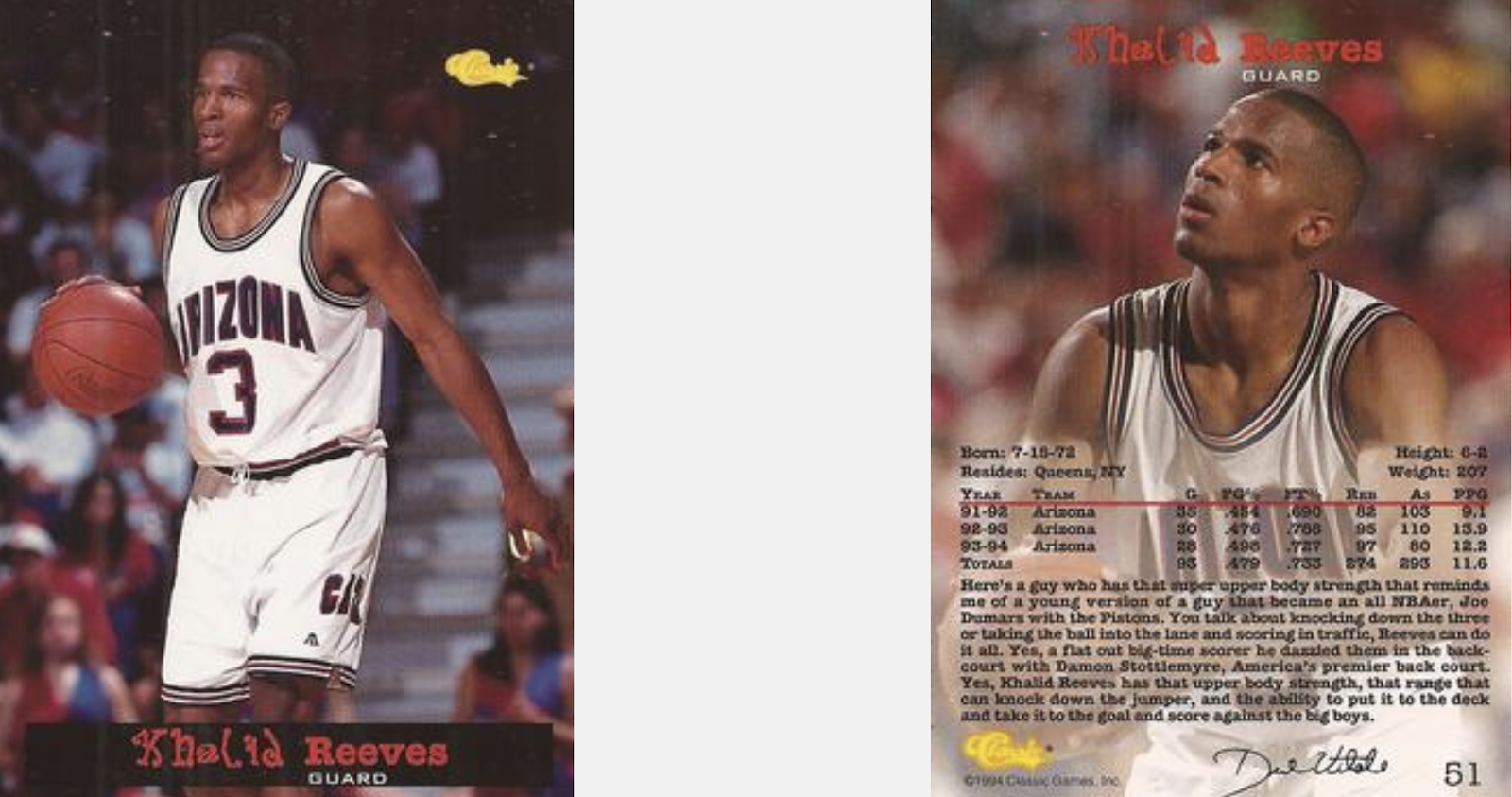

I played three games and then an American point guard I used to idolize showed up and started practicing with us—Khalid Reeves, the one that led Arizona to a Final Four with Damon Stoudamire. I was infatuated with the Wildcats as a kid.

“What’s up, man? I remember you from the Final Four. Where you from?” I asked.

“Queens.”

“Cool, man. Welcome.”

He didn’t say another word to me. Odd. Weird. What an asshole, I thought.

The next day after practice, the GM walked over to me and handed me a manila envelope. I looked up at him.

“What’s this?”

“Open it.”

Inside was $10,000 cash.

“You guys already paid me when I got here,” I said, confused.

“Yeah, this is for your departure. Thanks for playing with us.”

I looked across the locker room and the GM’s kids were playing with Khalid Reeves, a first-round draft pick and First-Team All-American. He was pudgy and out of shape and bald, and I didn’t like his game anymore. Plus, he waddled around like a fat, pigeon-toed beagle.

“Trevor. Hello?”

“Oh, sorry. Got lost there.”

“Do you have an agent?”

“No. No more agents for me. I want to stay in Belgium for the rest of my career.”

The muscles in my neck clenched and my intestines contracted in two. I’d gone through four agents since my rookie year. Most of them you talk to about four times a year—when you play great, when a higher offer comes in, when you play terrible and they are going to fire you, or when you call them because you haven’t been paid.

I thought of moving Meryl, my girlfriend. She was happy in Aalst. She loved it actually, just like I did. I thought of my younger brother, D2, my best friend whom I had on my contract to tryout. I thought of our dogs—Bear and Moxie—playing in our yard. I thought about all my friends in Aalst, Belgium, the ones that had let me stay with them when I drank too much, or let me crash on their couch, or pat me on the shoulder after a tough loss. We had gone from the second division to making the third-highest league in the world—the Euro Challenge—in three years.

“How many years is the deal?” I asked.

“Two plus one.”

“No, no more two-plus-ones. I want three years.”

Typically, the GM would never talk to a player directly. It would always be the agent’s job, but I was going to use my best friend from high school to be my agent and do the paperwork. But I was talking to someone that had one of the biggest GM resumes in Belgium. I turned over my shoulder, looking past his garden into a rare sunny day in Oostende. I could hear the faint sound of ocean waves. I’d get to live on a beach. I scratched my chin. And it was only forty minutes away from my brother.

The Belgian GM was the Jerry West of Belgium, I realized. In Europe, three-year deals are unheard of. He must really want me, I thought. Aalst, my current team, hadn’t even spoken to me about next year. And I had a good chance at winning a championship there and while making double the money. The visions of Aalst, my home, and where my MVP days happened escaped like thin, streaming strands of cigarette smoke out of the GM’s living room window.

“Trevor. Can I tell you something?”

“Sure.”

“In life, you are always paid for what you did the year before. You’ve had two amazing years in Aalst.”

“Yes. Thank you.”

“You’ve beaten us twice in the playoffs.”

“Yes. True,” I smiled.

“You’ll get paid a big signing bonus up front for what you’ve proven you can do.”

I thought about the money again. This was guaranteed. This wasn’t Poland…or Portugal…or Venezuela. Belgium had a working government, full health care, free schooling, and modern technology. I’d get all my money. I knew that much. I reached out my hand. He grinned and his hand met, and then clenched mine.

“Oh, check, cash, or wire?”

“Wire.”

Later that day, I suited up for my game still playing for the city and home I still loved in Aalst, Belgium. But it was just another day getting paid to play professional basketball.

Trevor Huffman is a former professional basketball player and contributor at Grandstand Central. His new podcast, “The Post Game” looks at the game after the game, as he speaks with retired athletes about life beyond sports. Subscribe here.

[…] could be different in the NBA, but it’s a fraternity of egos. I didn’t get in and instead, I roamed Europe with a knapsack and some dirty shit-stained underwear and stayed at hostels on the weekends. But I […]