At some point every fan witnesses a moment where a player does the unthinkable, a bone-headed play that leaves everyone — from fans, teammates, coaches, announcers to vendors — thinking “WTF ARE YOU DOING?.”

We’ve all been there and said — or more likely, screamed — those things.

Whether it was Zidane head-butting Marco Materazzi in extra time of the 2006 World Cup Final, Chris Webber calling a timeout he didn’t have during the closing seconds of Michigan’s NCAA championship loss to UNC, or Magic (“Tragic”) Johnsons’s series of late-game mistakes in the 1984 NBA Finals, fans have been tortured by last-second lapses of judgement and competence by highly-trained professionals for decades.

And now that you’ve had the chance to re-live some of the worst moments of your lives (you’re welcome) and hopefully calmed down, what if I were to tell you there’s a completely valid reason for those moments of madness and bone-headed-ness in high-pressure situations?

That reason can be found in the neuroscience of how pressure/stress/anxiety affects our brains.

In my last article, I wrote about how pressure affects and interferes with movement, leading to plays like Nick Anderson’s four-straight missed free throws. In this piece, I turn my attention towards how pressure affects memory and thinking.

I’ll kick this off with a quick look at the anatomical and physiological neuroscience basis, then apply that to direct examples (my apologies in advance for anyone who is directly affected by them), and finally, end with ways to train and guard against it happening.

Without further ado:

I. How memory works

Anatomy wise, all you really need to know is this: there are a bunch of different parts in the brain, working in conjunction, that are responsible for memory — it’s not a straight-line process.

Think about those times when you smell a certain smell or hear a certain song and you’re instantly transported to a specific memory…that’s incredible right? And it speaks to the complexity of memory.

There are three major steps in the process of creating and forming memory.

1 — Encoding

The first step in the process of memory is known as encoding.

This is when information from our senses is translated into a form that we process mentally. In other words, the stimuli that we’re receiving is re-packaged into a form that the brain understands.

2 — Storage

The second step is storage, or retaining information over time. There are 3 different types of memory storage.

The first type is called “sensory storage”. In this phase, a stimulus is determined to have meaning or not (in anywhere from 1/5 to 1/2 second). If it’s determined to not have meaning, it’s thrown by the wayside. If it does, the brain gives it attention and it’s moved over to the second type of memory storage, short-term memory.

Short-term memory consists of information that is currently in use — it’s akin to a “scratch-pad” for temporary recall and processing of information.

Generally, we can only hold five to nine items at one time, typically for 10–15 seconds. Try to remember more and we’re likely to forget the middle items.

Functionally, short-term memory isn’t used to remember concepts but rather as contextual links and indicators. For example, the words at the start of this sentence are being housed in your short-term memory and then associated with the words at the end of the sentence to give it meaning.

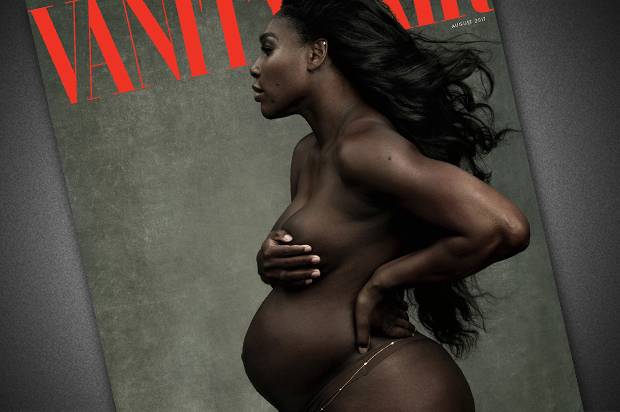

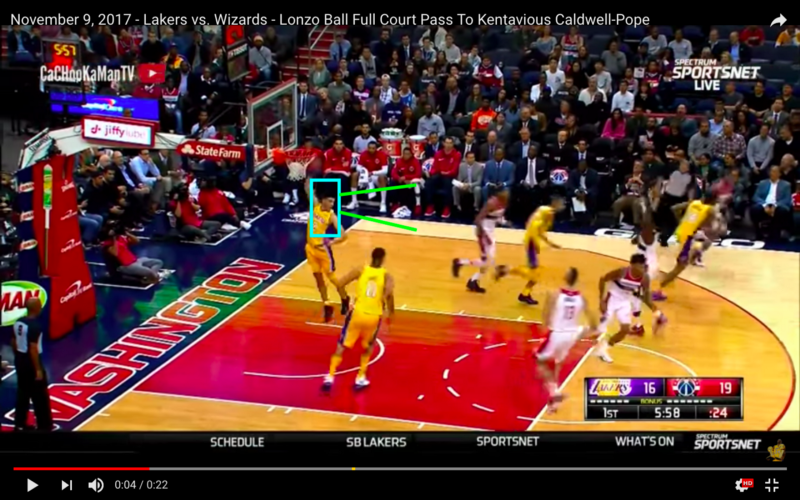

Other examples include quick math calculations where you hold numbers in your head or Lonzo Ball looking down-court before grabbing a rebound to take a snapshot of player positioning:

Additionally, when short-term memory is used to perform complex tasks, like reasoning and inference, it’s referred to as working memory. It’s applying the information you have in front of you to make the best choice possible.

The working memory of professional athletes is constantly tasked with making these inferences to inform quick reasoning and decision-making.

Using the above example of Lonzo — after he grabs the rebound, his working memory instantly infers player movement and potential passing lanes based off the short-term information he stored prior to grabbing the rebound. That results in his trademark instant full-court passes:

(Imagines Lebron on the other end of these. Fans self.)

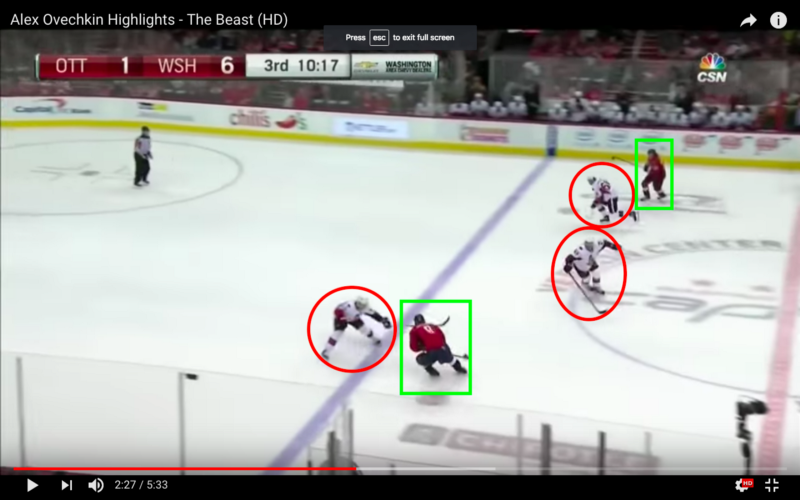

Another example is Alex Ovechkin. When he skates across the blue line into the offensive zone, the sights and sounds around him — like teammate positions and movement, defender positioning, time on the clock — are encoded and stored into his short-term memory.

Then his working memory begins to make inferences about player positioning and what to do next — Where do I have the advantage? What’s the defender taking away? Resulting in this decision:

So now moving back to the process of memory formation and storage types — unless we make a conscious effort to retain that short-term memory (like repeating a phone number or reviewing notes or film study), it’s lost. However, if the effort is made, that memory is transferred to the third type of memory storage — long-term memory.

Long-term memory is probably what most of us associate with memory — remembering things over a long period of time and being able to recall them days or months or years later.

There are multiple sub-types of long-term memory but that’s beyond the scope of this piece. If you’re interested, check out this excellent summary & breakdown.

After a memory has been consciously learned and transferred to long-term memory, the third and final step in the memory process is….

3 — Retrieval

The third step is retrieving those memories we have committed to long-term storage. There are two main methods: recall and recognition

A. Recall

Recall is remembering something without any cue needed. For example, if your friend asks you how many times has LeBron gone to the finals — you search through your memory and find the answer: 9.

B. Recognition

Recognition is remembering something by using an associated cue from something you’ve experienced before. This happens quite frequently in sports. Teams and players often run the same plays and have certain tendencies. Recognizing those situations based off prior experiences and understanding how to react can be the difference between winning or losing the game.

Now that we have a basic foundation of how memory works, lets focus on which parts of memory are most affected by pressure and stress.

II. How high-pressure, stressful moments affect memory and decision-making

There’s research showing that both short-term and long-term memory are affected by the increased stress, anxiety, and worry that can accompany high pressure, “clutch” situations.

Specifically — working memory, the retrieval component of long-term memory, and updating long-term memory (termed “re-consolidation”) are affected.

Let’s start with…

1 — Working Memory

Excessive stress has been shown to impair working memory, leading to mistakes in remembering short-term items like…..what the score of the game is. Leading to plays like this:

Additionally, impaired working memory leads to not remembering or processing context clues, a higher degree of reasoning mistakes, and more “false alarms”. This results in impaired, less-effective decision-making.

Whenever I hear someone say that a player isn’t “reading the game well”, impaired working memory is what comes to mind (unless it’s a commentator speaking about a black QB, that’s a whole different topic).

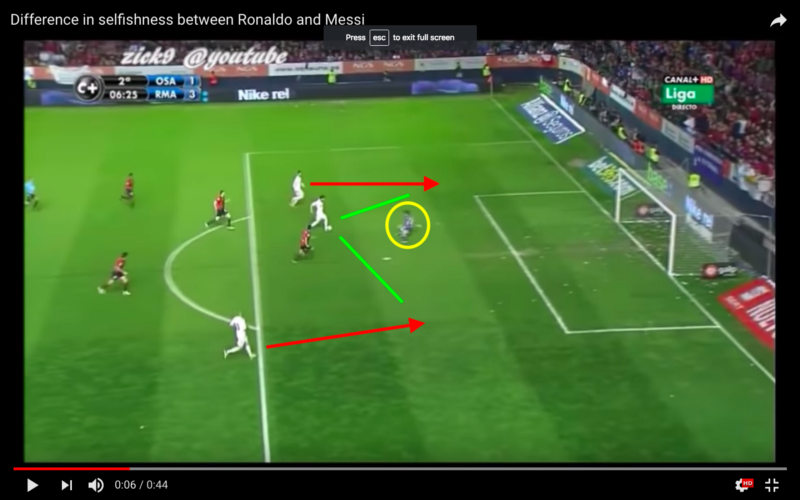

Look at this example of Real Madrid on a 3 v 1 break:

Gonzalo Higuain has the ball and the keeper is off his line, completely committed. Gonzalo has the really easy option of laying the ball off to his left or he can even lay it off to his right — both resulting in open net chances.

Here’s the decision he makes:

Oy vey.

Research has shown two underlying reasons for these impairments in working memory.

The first is a physiological basis. Acute (immediate) stress reduces activity in a part of your brain that is critical for working memory, known as the pre-frontal cortex (PFC).

The second is procedural, known as the distraction theory. Being distracted takes attention away from the task at hand and directs it towards irrelevant stimuli like worry, stress, and anxiety. This theory is supported especially in those situations where working memory is used to make quick decisions, which applies to any active phase of sports.

That’s the primary way stress and anxiety lead to “bone-headed” mistakes, and here’s the second…

2 — Long-term memory retrieval

Excessive stress has also been shown to affect long-term memory retrieval, although to a lesser extent than working memory.

While you’re in a stressful situation, it’s harder to remember information that you’ve previously committed to memory.

Have you ever studied hard for a big test but when the moment came, your head went completely blank? That’s stress affecting the retrieval of long-term memory.

The mechanism behind this deficit in long-term memory retrieval stems from cortisol (“the stress hormone”) blocking memory receptors which make it difficult for the brain to find the right connections. Depending on the level of stress, this delays the retrieval response or makes it impossible until the stress level ratchets down.

3 — Updating long-term memory (“Re-consolidation”)

Long-term memory is typically malleable — you can learn new information and update the prior memories. However, research shows that stress and anxiety from high-pressure situations disrupt this process.

This integration of new information and updating is critical in sports. A high-level opponent is likely to have some tricks up their sleeve and add in new layers to their strategy — like switching a formation in soccer or adding in a new wrinkle to the defensive pre-snap coverage.

In these situations, previously held long-term memories are challenged and presented with new information — processing and integrating this information is key to adapting and staying a step ahead of the opponent.

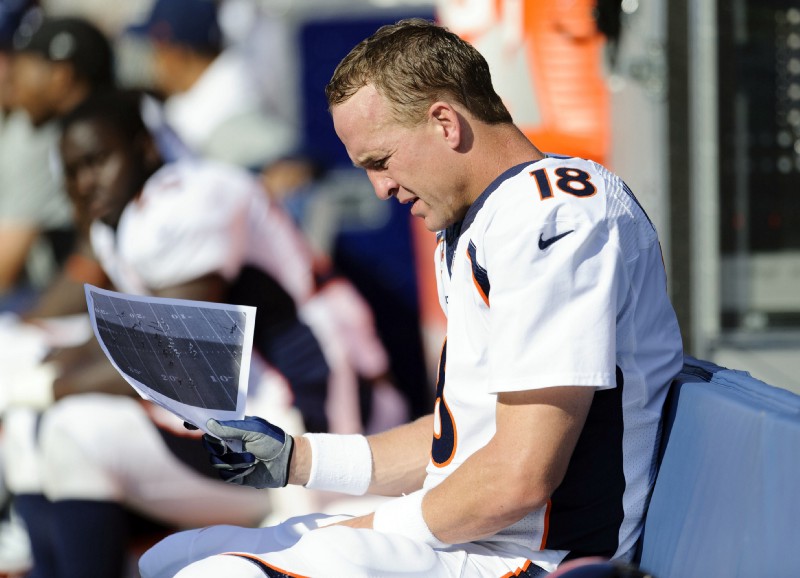

In turn, the opponent now has to reconsolidate and adapt — it’s like a constant game of Pong. That’s why you’ll often see NFL players reviewing film or pictures on the sidelines after a stalled offensive drive or defensive mix-up:

Gotta re-consolidate bro.

When stress interrupts that process of updating memory, you have examples like Hungary’s six to three thrashing of England in a 1953 game dubbed “The Match of The Century”.

In this game, Hungary took two conventional norms and completely flipped them — leading to mass confusion amongst the English players.

First, Hungary’s central striker termed a “#9” because that’s the number given to the primary striker, Nandor Hidegkuti dropped into the midfield away from England’s main central defender, Harry Johnston. Hidegkuti found himself playing in acres of spaces, constantly feeding the ball to the other forwards, and dictating the game.

Secondly, Hungary’s holding midfielder, Jozsef Zakarias, dropped deep whenever England had possession — acting as a second central defender and pushing the full-backs out wider, as we see in the modern game. This approach of a four-player defensive line soon spread and became the default.

If you’re interested, here’s a video recap of the match:

England had prepared for the old system and couldn’t adapt to the new strategy, getting creamed in the process.

The mechanism behind this inflexible long-term memory is similar to what I described above for the deficit in long-term retrieval. When the stress response kicks on, cortisol (“the stress hormone”) blocks the receptors needed to re-consolidate information; specifically, it blocks two parts of the brain called the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Alright, so we’ve broken down the effects of stress and anxiety into its memory components, with examples, but now lets go through a couple plays and decisions that paint the entire picture of how working memory and long-term memory retrieval can be the difference between “wow, great play” vs a “WTF” play.

III. Some examples

A. First, an example of a “wow, great play”

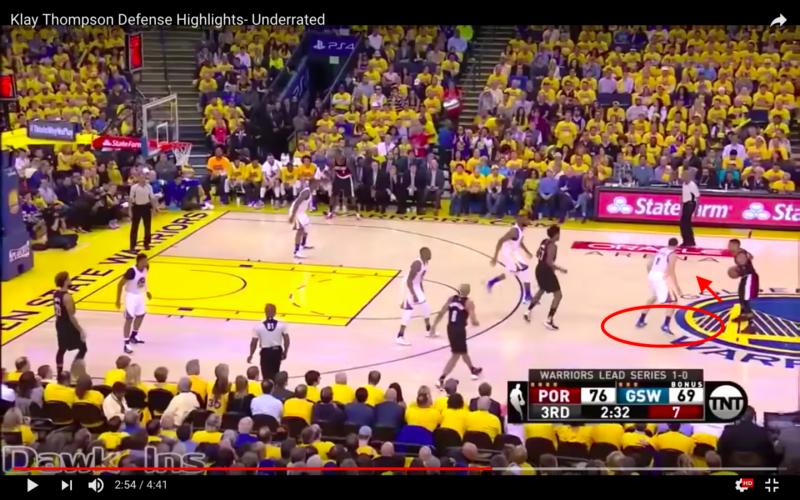

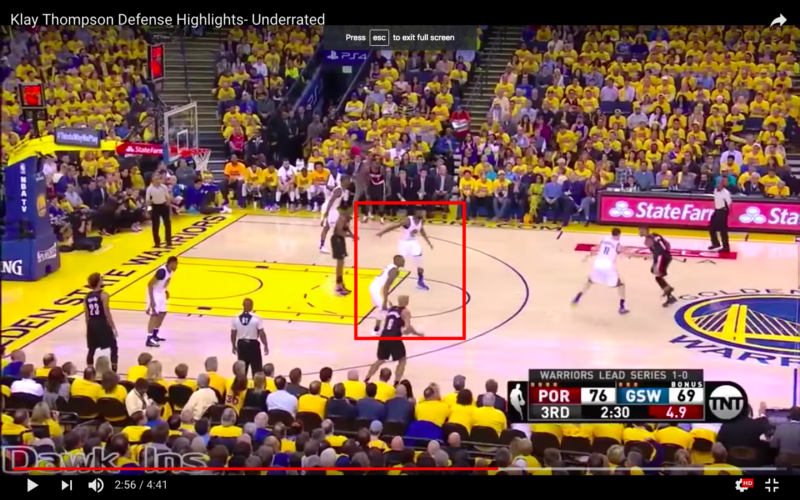

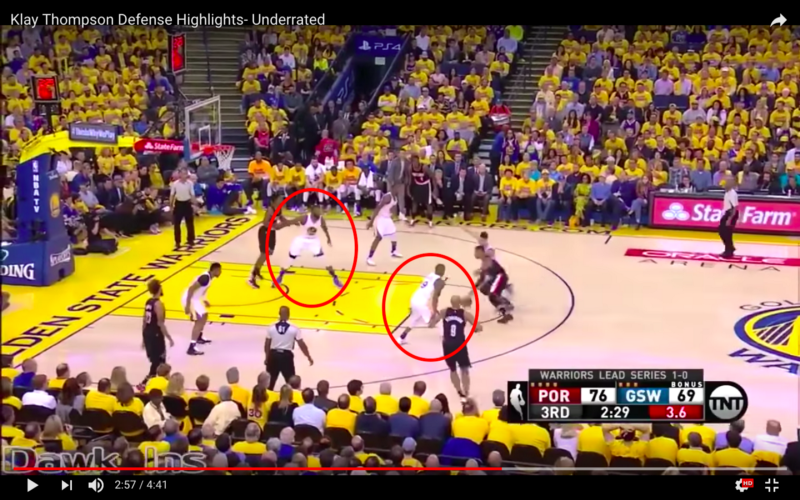

Let’s use the example of Klay Thompson defending Damian Lillard on the perimeter during a playoff game in which the Warriors are down 7 late in the third and need stops to get back into the game.

1 — The play starts with a potential pick and roll setup between Lillard and Portland center Ed Davis. Klay peaks over his left shoulder to see Davis recognizes the play (long-term recognition), and instantly reacts by shading Lillard away from the screen:

2 — This negates the pick & roll and Ed Davis returns to the paint. At this point, the play turns into a 1v1 on the perimeter, with Klay using his working memory to know that he still help behind him on both elbows (with Ezeli trailing Ed Davis into the paint and Iguodala being on the right elbow from the start of the play):

3 — Now, another working memory aspect and two recognition aspects come into play, one general and one specific to Lillard.

First, Klay’s working memory knows the shot clock is running down so Lillard has to make a move relatively quickly.

Additionally, Klay knows that a perimeter player in basketball is taught to attack and beat the defender by trying to get their shoulder and body past the defender’s lead leg — this is called “killing the lead leg”.

Lastly, Klay knows Lillard loves to drive to his left because it gives him the option of quickly pulling up for a jumper with his shoulders already square to the basket or getting to the basket.

Klay knows these tendencies because he’s experienced them before and has seen plenty of tape — they are stored in his long-term memory. When Damian crosses over from right to left and attacks Klay’s right foot(which was staggered above his left foot), Klay is ready and quickly reverses his stance:

4 — As Lillard drives to his left, Klay’s working memory again informs his decision-making. He knows the shot clock is getting really low, Iguodala is on the right elbow, and Ezeli is in the paint:

Igoudala being on the right elbow takes away Lillard’s favorite left-handed step-back jumper and Ezeli being in the paint forces Lillard into a tough contested lay-up which you’re ok with.

Therefore, Klay’s responsibility is to be ready for a dribble pull-up or floater in the lane. That’s exactly what happens and Klay is ready for it, forcing a contested floater:

This quick defensive decision-making based on fluid working memory and long-term recognition, regardless of pressure or stress, is what makes Klay an elite defender.

Don’t let Klay’s demeanour hide the fact that’s an incredibly sharp player — Mychal Thompson didn’t raise no fool. I could watch him and Draymond play defense all day — incredible decision-making.

Now let’s look at the other side of the coin, cringe-worthy moments that I have trouble watching: long-term recognition and working memory gone wrong in a big pressure moment.

B. WTF play

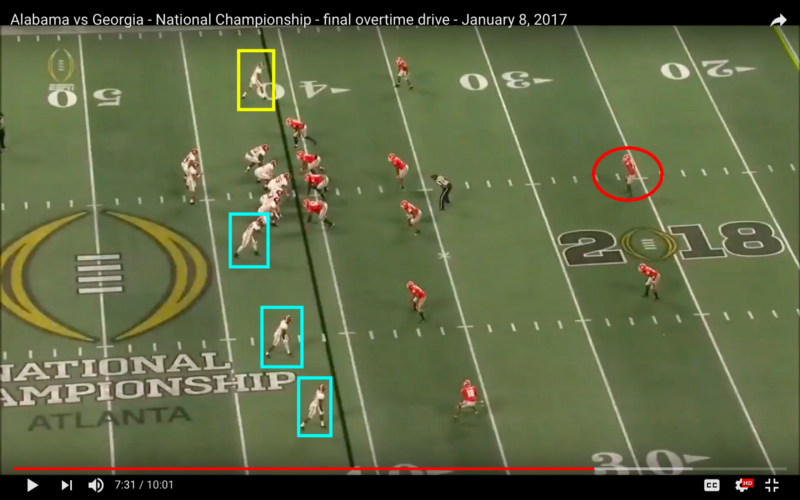

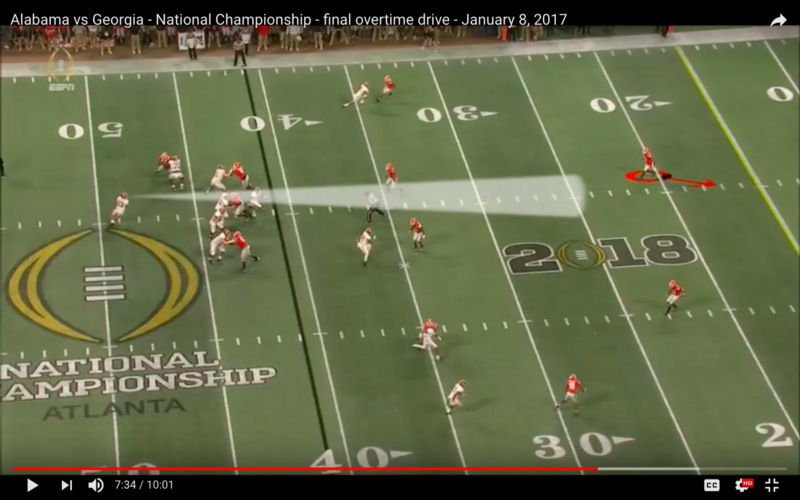

The play we’ll look at in detail is Alabama’s game-winning touchdown against Georgia in the 2018 CFB Championship, specifically the role of Georgia safety Dominick Sanders.

Let’s start with pre-snap reads:

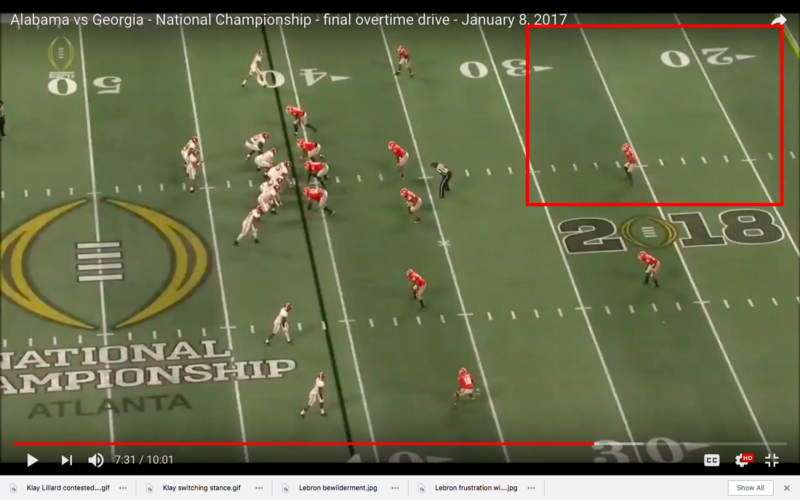

1 — For Sanders, the play starts with long-term retrieval. Alabama’s in a long-down situation (2nd and 26) and comes out with trips to the right with one wide-receiver on Sanders’ side. Take a look (Sanders is circled in red):

2 — Based on long-term retrieval from film and play study combined with Georgia’s play-call, a cover-2 zone where the safeties split, Sanders should know he has deep route responsibility of his side of the field. Here:

After the ball is snapped, Sanders shifts predominantly to working memory.

He’s tasked with using contextual indicators and clues (often referred to as “keys”) to make quick decisions. The offense is trying to distort these keys by throwing out information that isn’t relevant.

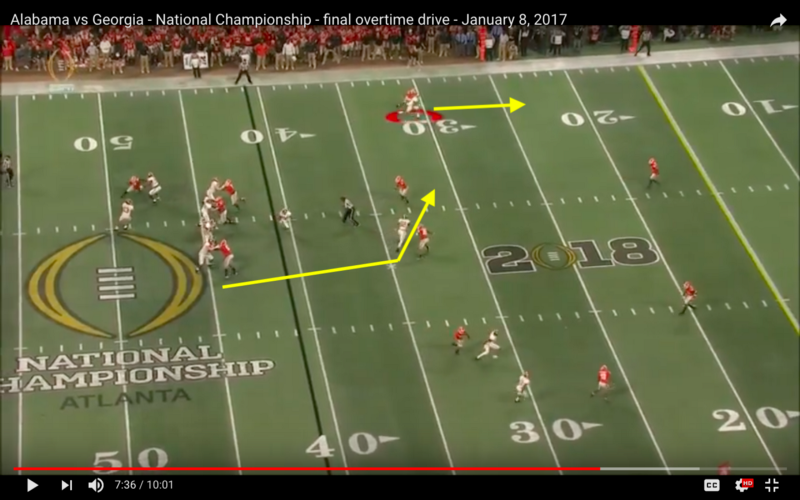

1 — First, Sanders has to figure out the routes that are possibly coming into his area of responsibility, and the positioning of his teammates. In this case, there’s a fly route on the outside and a shallow post breaking to the outside as well:

2 — Based on his deep coverage responsibility and the working memory reads of the two routes in front of him — both routes breaking to the outside of the field but the shallow post being covered well by his two linebackers — Sanders should start shading to the fly route.

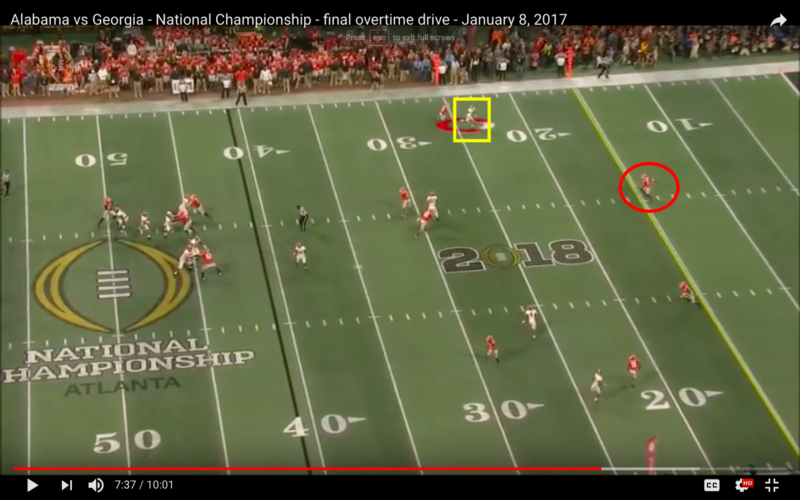

However, he continues toward the middle of the field and finds himself in no man’s land — way too far in the middle of the field to close down the fly route:

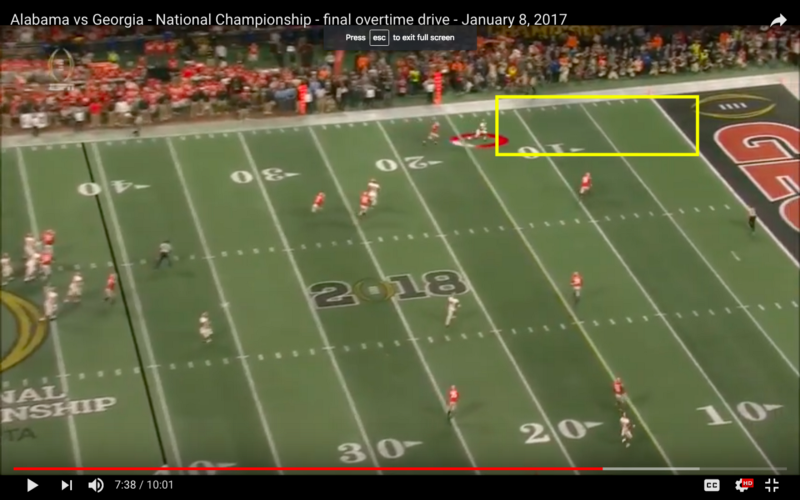

3 — His deep, over-the-top responsibility is compromised, creating this huge catch window:

That’s like taking candy from a baby. The Alabama true freshman QB — Tua Tagovailoa — makes a strong throw and it’s all over except for the fat lady needing a triple bypass heart surgery from too much singing.

When I saw this play live, I figured there had to be a blown coverage because the outside cornerback for Georgia is playing trail technique which means he’s fully expecting there to be help over the top. Either the cornerback messed up or something else.

Then I saw the overhead all-11 view…Sanders blew that coverage. As a connoisseur of all things strategy and analysis, I couldn’t help but wonder “WTF ARE YOU DOING OUT THERE SANDERS…AND WHY”.

It’s possible Sanders couldn’t retrieve and recognize Alabama’s formation in the pre-snap read. Additionally, his working memory may have been distorted, leading to him ignoring his key indicators like “where are the routes headed? Are they covered by my teammates or my responsibility?”

Additionally, as I noted above, working memory can lead to a “higher degree of false alarms”. In football terms, this means paying attention to the wrong keys — the opponent is always using disguises and traps to throw you off the scent.

In this case, that trap was Tua’s eyes. Tua intentionally looked down the middle and right side of the field to try and “hold the safety”. Sanders, instead of blocking out this irrelevant “false alarm” stimuli, relied on it and ignored the relevant route pattern and teammate positioning keys in front of him.

The result was Sanders drifting to that place no safety ever wants to be, the elephant graveyard of football….

….No man’s land:

Impaired long-term retrieval + impaired working memory = Roll Tide.

In both of these plays, there’s ideally a mixture of fluid long-term retrieval and working memory throughout. Long-term retrieval informs the general outline and tendencies while working memory informs the specifics of that exact situation.

With Klay, retrieval and working memory are operating fluidly and efficiently to inform decision-making whereas, with Sanders, they are impaired. The inferences and decisions within the play reflect that, leading to two completely different outcomes.

So how can athletes improve or guard against the impairment of memory and decision-making during crucial stress-ridden situations?

IV. Training & Prevention

Generally, any technique or strategy that limits or decreases stress, anxiety, and worry will bolster memory and decision-making in clutch situations.

I gave a variety of these techniques in my last piece.

Additionally, there are two promising training and prevention techniques that can support memory function under stressful conditions.

1 — Forced Retrieval

Forced retrieval is a specific way of studying. It forces you to actively retrieve information rather than passively process it.

A common example of forced retrieval is flash cards. Every time you see the flash card, you have to actively recall and retrieve the content. Compare that to reviewing or re-reading notes where you can just passively scroll & scan down the page.

Research with students shows that flash cards — especially when randomized — are far more effective for studying and maintaining information compared to reviewing notes.

For any students or anyone who wants to learn and maintain new information, there’s a randomized note-card program called Anki which is a must-have.

Additionally, learning via active retrieval has been shown to protect against stress-induced memory deficits.

For example — let’s say instead of reviewing game film, Georgia coaches made safety Dominick Sanders go through randomized clips and write down the formation and potential route combinations every time.

This may have improved his ability to retrieve that pre-snap information while under stress, inform his decision-making, and put himself in a better position to break up that fly route (and not crush Georgia’s hopes and dreams).

The second training and prevention technique is…

2 — The “Dual n Back” task

The “dual n back” task has consistently been proven to improve working memory by training attentional focus. In other words, it makes you better at figuring out what information is relevant or not relevant to the task at hand.

The way the game works is that you listen to streams of letters and simultaneously look at a changing grid of squares. Whenever the current letter or highlighted square is the same as the one that occurred a certain number of items earlier in the stream, you press a key. The difficulty is intensified by having to compare the current square and letter with items further back in the stream.

This exercise forces you to focus on multiple working memory inputs (the letters and grid of squares) and rule out information as relevant or not (hitting a key only when they occur again).

You can try it here.

This improvement in working memory from the “dual n back” task has been shown to be true under stressful conditions as well, mitigating some of those working memory deficits.

Maybe all JR Smith needed in that game 1 of the 2017 Finals was an Ipad with the “dual n back” game and his working memory of the game score wouldn’t have failed him…and Lebron wouldn’t have punched a blackboard his way to getting swept and leaving Cleveland.

Thanks for reading and until next time.