How a player performs in high-pressure situations can make or break their careers, their reputations, and the aspirations of their team and fanbase. When it all goes wrong, you get comments like:

“What a choke artist”

“He’s not clutch.”

“You can see him over-thinking it out there.”

“They’re trying way too hard.”

These differences between how players respond during pressure spots led me to the question: what separates the clutch players from those who choke? Is there something different about how they think, are there differences in personality, are their differences in how they train for those moments?

I came to find that there’s a neuroscience basis to why a player “chokes” and responds poorly when the pressure/stress (I use these two interchangeably) ratchets up.

This basis can help explain and get to the root cause of things like Lebron’s hesitancy in the 2011 NBA Finals, Rory McIlroy’s “5 hours of choking” at the Masters in 2011, and Buckner’s basic blunder in ’86 (It’s ok to talk about that now, right Boston fans?).

There are viable reasons for each that go beyond not having the legendary “clutch gene”.

My goal with this piece is to explain those types of moments through that lens of neuroscience— specifically, how stress affects sports movement and impairs thinking/memory while taking into account the role of personal factors, training strategies, and preventative measures.

I’ve split the topic into two different pieces:

1 — This piece analyzes how pressure/stress affects movement

2 — The next piece will examine how pressure/stress affects thinking/memory.

To begin to understand why players “choke”, let’s start with a basic foundation of neuroanatomy and then a rundown of motor (movement) control and motor learning.

I. Neuroanatomy Basics

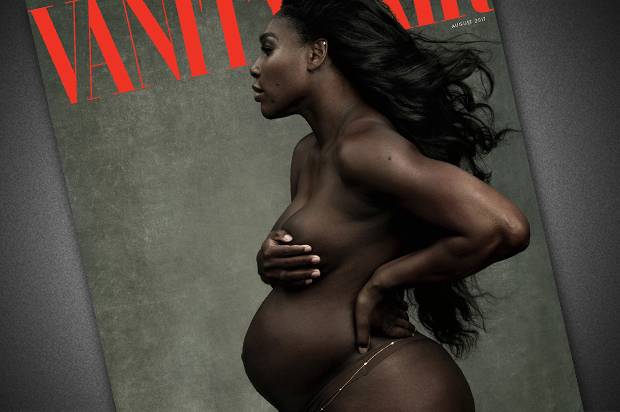

A. Neurons

Let’s start with the basic building blocks of your nervous systems — neurons. Every tissue of the nervous system is comprised of neurons. Here’s what they look like:

They form a messenger system that functions like a game of telephone — each submits a message from one neuron to the next using little chemicals called neurotransmitters until that message reaches its target destination.

Here’s a cool picture and videos that show how neurons transmit signals to each other:

B. The Central and Peripheral Nervous System

1 — Anatomy

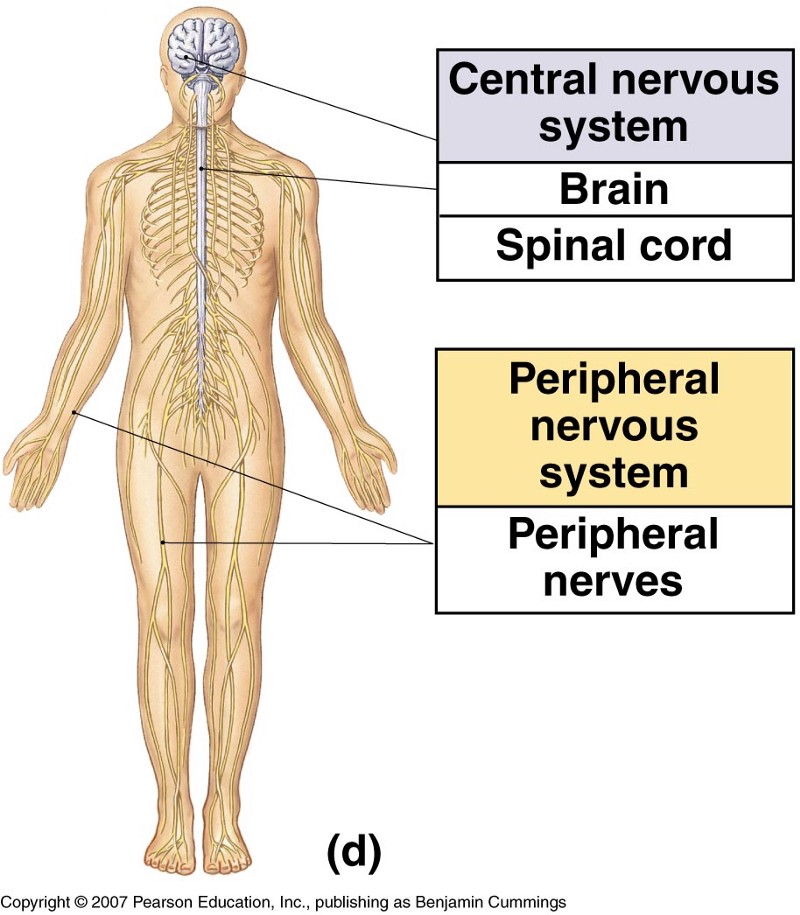

Humans are split into two different nervous systems: the central nervous system (CNS aka the brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system ( all the nerves except the CNS — which includes anything into your arms, legs, skin, etc).

Here’s an anatomical overview:

Personally, I use the analogy that the brain is a big lake and the spinal cord as the huge river that flows out of it. Out of this river flow countless smaller streams (the peripheral nervous system) into distant places.

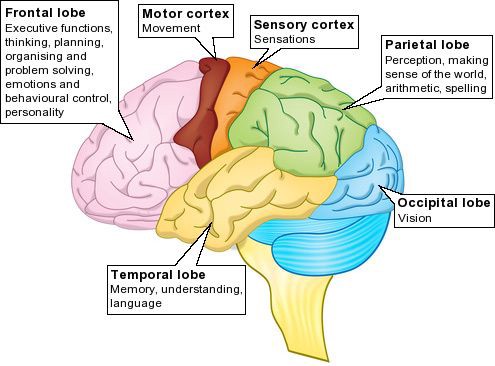

Additionally, the brain itself has key regions called lobes and cortexes — here’s a great visual:

For our purposes, the frontal lobe, motor (movement) cortex, and sensory (sensation) cortex are important to note. Speaking of movement and sensation, here’s how they function within the nervous system…

2 — Function (sensation and movement)

I think of the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord or CNS) like the commanders of an army and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) as the troops. The commanders get information from the troops, process it, and decide on actions. The troops are responsible for gathering information and executing the orders issued by the commanders.

The generals and troops are segmented into one of two categories that determine the type of information they can receive and the orders they can execute. These categories are sensory (sensation) and motor (movement).

Sensory

A sensation is an upwards process — from the troops to the commanders. Some stimulus (whether that be touch, temperature, taste, smell, interoception aka the sense of the internal state of the body, often referred to as the “8th sense”) activates the troops (sensory receptors in the PNS) which pass it along up the chain to the commanders (CNS) who then process that information and identify what it is.

For example, when Lionel Messi is waiting to receive a pass from his midfielder and a defender’s arm brushes up against him — specific receptors capture that information and send it up to specific parts of the spinal cord and brain. They process the information and determine that it’s “touch”. This entire process occurs along a defined sensory pathway.

Motor

Movement is a downwards process — from the commanders to the troops. The commanders decide what movement they want to execute and then pass it down the chain (motor pathway) to the troops.

When Marc-André Fleury wants to raise his glove hand to stop a puck, a specific part of his brain activates, the message is sent down to his spinal cord, and then out to the specific muscles that are responsible for that specific movement. This process occurs along a defined motor pathway.

Combined

Sensation and movement often intertwine. Sensations inform movement and vice-versa — it’s like an adaptable network.

Arnold let us in on this secret years ago:

To illustrate this constant interplay, let’s use the example of Tom Brady dropping back into the pocket. After the snap, he takes a 5-step drop, plants the back leg, and sits in the pocket. His sensory receptors pick up a vibration off his left side (“pocket awareness”) which informs his central nervous system and results in a motor reaction — “climb up into the pocket”. As he’s taking those steps up, his sensory receptors are constantly feeling for more information around him. As the pocket begins to close down, his visual movement patterns increase to find an open receiver.

It’s a constant feedback system between sensation and movement, one informing the other. More often than not, it allows Brady to get the ball off…except when Brandon Graham is barreling down on him too quickly and smacks his arm to cause the empty-hand game winning fumble…

For the intents and purposes of this piece, let’s focus on movement — specifically on the neuroscience of how we move (motor control) and how we get better at movement (motor learning).

C. Motor control and motor learning

Motor control refers to the process through which we activate and coordinate our muscles and limbs to complete movements.

As I mentioned above, each movement occurs along a specific motor pathway — transmitting from the brain to the spinal cord to the specific body region.

When Kobe took two dribbles from the 3-point line and rose for a fadeaway at the corner of the pain to beat the Suns in game 4 of their first-round playoffs:

That’s an established and defined motor pathway that he’s worked on literally thousands (if not millions, this is Kobe after all) of times.

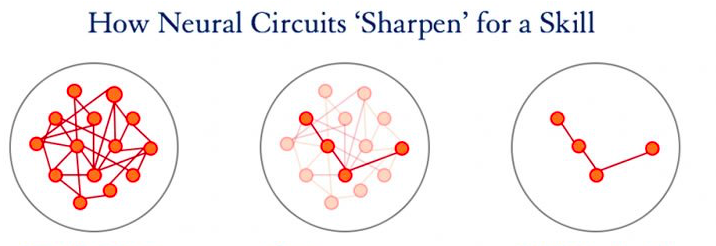

However, when he was first learning that movement sequence, these motor pathways weren’t well defined — they were filled with “neural noise”. Over time, as he continued to practice that specific movement, those pathways become increasingly defined with less “neural noise” — resulting in a more efficient and effective movement.

Here’s a good visual of that process:

This increased efficiency and effectiveness of neural transmission is quite powerful — for example, research has shown that when you’re doing a new lifting pattern at the gym (like a squat or deadlift, etc), the gains in the first 2 weeks are almost exclusively from this neural adaptation and not an increase in muscular strength.

This is termed neuro-muscular adaptation — the neurons are getting better at activating the muscles and limbs which results in improved coordination and movement.

The more complex the movement and the longer you’ve been doing the previous motor pattern, the longer and more repetitions it takes to learn and change it. For example, it can take years for an NBA player to undo the jump shot they’ve been using most of their life and re-learn a new one. (So stop assuming Ben Simmons can pull this off in a few gym sessions).

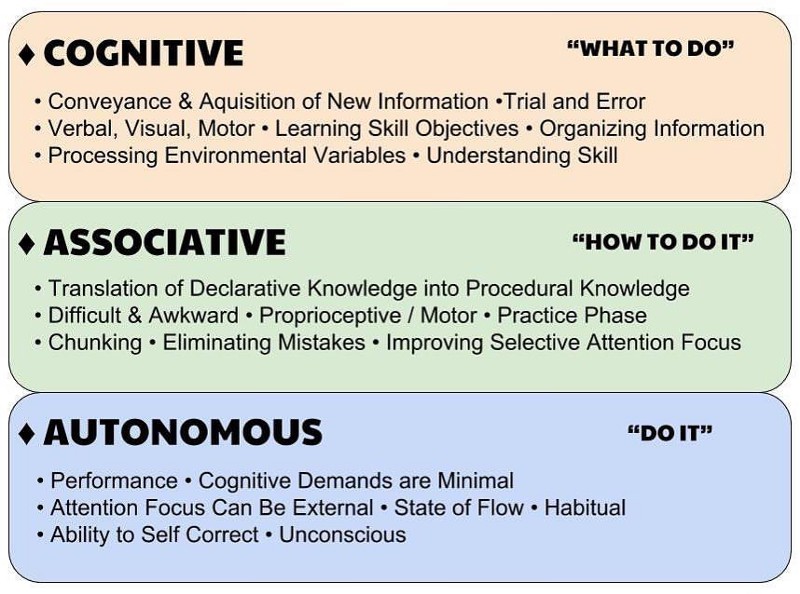

Within this process of motor learning, there are three stages:

These stages are fluid and you can shift back and forth between them, with progress oscillating day to day. For example, this past season Lonzo showed a handful of instances where he pulled-up off a right-handed dribble with a modified jumper. However, he wouldn’t do it again for weeks at a time.

These inconsistencies and mistakes made along the way are crucial for learning and figuring out what works and doesn’t work (reducing the “neural noise”)

Here’s the analogy that comes to mind for me:

You’re a rookie and you’ve just been drafted. Your daily tasks/routines are completely thrown off — you have to get a new gym, a new grocery store, bank, you don’t have “tutors” to do your bidding anymore, so you have to figure out the best times that work within your practice schedule, traffic patterns, Fortnight schedule, etc.

At first, it’s like guess and check — you’re a little scattered, figuring out what does and doesn’t work for you, driving all over the place, making a bunch of mistakes — it’s inefficient and there’s a lot of noise.

Eventually, you start to adapt and figure out quicker ways of getting around, choose the grocery store, gym, shops, but you’re still making some mistakes.

Until finally, you’re completely honed-in and set on a routine that works best and your routine is like a machine — you scoff at the tourists and newbs in the city who ask you for directions or eat at the knock-off halal cart.

So that’s motor control and motor learning. There’s one more thing you need to know — arguably the most crucial piece of the puzzle:

D. Internal and external cueing

We used to think that the best way to cue movement (internal vs external**) changed as you progress through the three stages of motor learning.

**Internal cueing is a step by step explicit breakdown of each part of the movement. External cueing is focusing on an external factor and outcome.

In the cognitive (beginner) phase, it was thought that cues needed to be internal — break down the movement into parts and think about each movement:

“Okay, square my feet to the basket.”

“Guide hand on the side of the ball, shooting hand underneath with finger-tips on the ball.”

“Get my eyes on the basket and back rim.”

“Slightly dip the hips and bend the knees and then with the elbow in, bring the ball up above the forehead.”

“Release the ball smoothly, up and out, 1-motion. Follow through with my pointer and middle finger going towards the basket.”

“Hold the follow through with wrist down, track the ball.”

For example, if Ben Simmons wanted to overhaul that jumper, he would’ve started with this type of training (can only imagine the amount of flack Ben would have gotten for it if his Dad was a loudmouth…).

Then, as you progressed to the associative (intermediate) phase and the movement becomes less disjointed and natural, optimal cueing was thought to be a mix of internal and external focused:

“Set my feet.”

“Eyes on the basket.”

“Up and out.”

“Hit the shot.”

“Hold the follow through.”

This is the stage that Brandon Ingram is in with his revamped jumper. He’s getting more and more fluid with a 1-motion release, still has instances where he will hitch, but shows consistency in high-stress situations as well, like this game-winner at Philly (also take note of Lonzo’s calm decision-making in traffic):

Lastly, once you hit the autonomous (expert) stage where the movement is automatic and ingrained, the cueing would become exclusively external:

“Hit the shot”

Steph Curry comes to mind — no thinking, but just shoots and lets his trained motor pattern do the rest. In fact, according to SportsScience, the only variable that Steph changes on his shot — to account for distance — is wrist speed. That’s why his jumper is so consistent and pure, he’s not interfering with his expert motor pathway.

The common thought was that a mismatch of cueing strategy and motor learning phase leads to poorer outcomes. However, the research increasingly shows that external cueing is the most effective regardless of the learning phase.

Whether you’ve practiced a movement millions of times or just a few times, using internal cues is going to reduce performance. That’s because internal cueing interferes with and reintroduces “neural noise” to those motor pathways.

Guess what pressure/stress/anxiety do to your cueing….

II. Why movement can “choke” under pressure

Remember Nick Anderson in game 1 of the ‘96 Finals? Needed one free throw to make it a two-possession game (forward to the 8:30 mark):

How about Blair Walsh missing a 27 yard FG from the left hash to win the Vikings’ NFC wild-card game against the Seahawks?

Or Darius Washington Jr. in the ’05 Conference-USA championship game, three free throws for a ticket to the Big Dance:

These are all prime examples of movement “choking” under stressful conditioning. There are a bunch of ideas out there as to why this occurs but I found two models and a handful of contributing factors to have good evidence behind them.

Let’s start with the models:

1 — Over Arousal

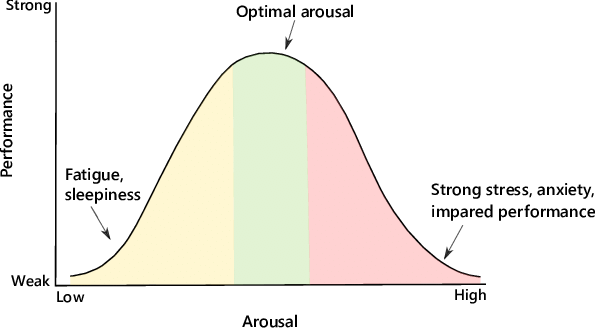

Changes in movement and motor performance have been linked to “excessive arousal” that is caused by high incentives, emotion, and social pressure — this is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law.

The basis of this law is that there’s an optimal level of arousal for performing tasks — too little or too much arousal and performance of the task will suffer. It’s like Goldilocks, you want arousal to be “just right”.

Research shows two scenarios that contribute to this “over-arousal”: excessive motivation and aversion to loss; it can be argued that these are two sides of the same coin, really hard to tease apart.

Motivation and aversion to loss come in many forms: winning the game, monetary incentive, emotional happiness or sadness and also in the form of protecting upholding our self-image.

We all want to look good in front of others and live up to their evaluations and expectations — to prove something. In other words, social pressure. As the stakes of a game get higher, the incentives, emotion and social pressure also get higher.

This instantly reminds me of Lebron’s play in the 2011 Finals when he came under criticism for choking and being disinterested.

This social pressure was explicitly mentioned during Lebron’s 2012 Finals MVP conversation with Stu Scott. This interview is one my favorites of all time — it confirmed all the qualities that make Lebron, in my opinion, the best player of my generation (I felt that way even before he became a Laker). Here’s a snippet:

Stuart Scott: “You said last year you were trying to prove something, and this year you realized you didn’t have to do that. So how do you re-focus your mind?”

LeBron: “I went back to the basics. My first seven years I just went out and the let game take care of itself…but last year, I tried to prove something to everybody…I played with a lot of hate and that’s not the way I play the game of basketball.”

Neuroscience research has shown this kind of ‘over-arousal’ would inhibit Lebron’s frontal cortex (pre-frontal cortex to be exact) and activate his brain’s reward pathway which involves the neurotransmitter dopamine. If you don’t recall, neurotransmitters are how neurons transmit signals and talk to each other.

This combination of events — the increase in dopamine during high stakes situations and inhibition of the frontal cortex resulting in diminished executive control like high-level decision making, planning, perspective taking, etc — has been linked to erratic movement and decreased performance.

2 — Explicit monitoring

In the “motor learning and motor control” section, I mentioned how internal cueing can interfere with movements. That’s especially the case with individuals who have mastered a complex movement and are in the automatic or expert phase of motor learning.

That idea is explained by “explicit monitoring”, also referred to as self-focus or execution focus. As in-game pressure ratchets up, self-consciousness and anxiety about performing well ratchet up as well. This increases the attention paid to the step by step process of the skill(internal cueing). Research has shown that this results in a regression to erratic and inefficient movement.

For example, Bill Buckner in game 6 of the 1986 World Series:

“Ok, here comes the grounder, I have to make this play. Let me get my feet square to it, bend my knees, glove in position, reach down…shit, what just happened”

Further, a really cool research piece showed how golfers performed better when their attention was drawn away from execution. Here’s what lead researcher Sian Bellock, associate professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, had to say:

“My research team and I have found that highly skilled golfers are more likely to hole a simple 3-foot putt when we give them the tools to stop analyzing their shot, to stop thinking…highly practiced putts run better when you don’t try to control every aspect of performance.”

Somebody should have told John Daly:

Now that we’ve covered the two main models, let’s review the personal factors that can make an athlete more or less likely to fall into these….

…cognitive traps.

III. Personal factors

There are a handful of personal variables that make each athlete more or less prone to choking.

1 — Aversion to loss

“I CANNOT lose this match, I CANNOT lose this match, I CANNOT lose this match”

The more loss-averse you are, the more you’re concerned about losing what you have. This was one of the main factors contributing to the “over-arousal” model I mentioned above.

The Falcons in Super Bowl LI come to mind (sorry Falcons fans reading this). Up 28–3 and completely changed their playing style — playing not to lose rather than playing to win shifts the emphasis on loss aversion rather than accomplishing victory.

Over-arousal on line 1.

2 — Fear of negative evaluation (FNE)

FNE is a measurable psychological characteristic that quantifies how apprehensive you are about others expectations of your or your own expectations of self. This was also one of the main factors (social pressure) contributing to the over-arousal model.

3 — High self-consciousness

“Am I doing this right?”…..”I wonder what they’re thinking”

Individuals with higher self-consciousness are more prone to focusing on internal cues (explicit monitoring) and creating social pressure anxiety by worrying about what others are thinking of them.

Rory at the 2011 Masters is a prime example and he was brutally honest about it months later:

“On that Sunday of the Masters I remember turning on ESPN to find people talking about me. I switched over to the Golf Channel and people were talking about me. It was hard to escape. Greg Norman said something to me afterwards that stuck; that any outside influence you let into your bubble can be detrimental, even if it’s just an article in a newspaper.”

This is a dude who allegedly once had a Google alert on his phone about any story that had his name on it.

4 — Low resiliency

Resiliency characterizes how well you’re able to bounce back and get over a setback. Poor resiliency results in higher anxiety and constant reinforcement of stress-failure conditioning loops.

As an example of high resiliency, I’ve heard many high-profile NBA players — most recently Steph Curry — say or echo the idea that “you can’t make a shot that you don’t take”. Don’t let misses and failures dictate your next actions.

So if we know the models and personal factors that contribute to movement choking, can we prevent or guard against them? We can certainly try.

IV. Choke prevention

The first step is to chew your food 24 times prior to swallowing. But seriously, the general principle is to use activities and training that help reduce anxiety, worry, and stress during the activity.

This includes:

1 — Reframing

Reframing is shifting how you view a situation or event — transform a negative, worrisome match into a positive, exciting match.

Instead of “crap, we’re down 3–1 to arguably the best team of all-time”, that shifts to “we have a chance to make history — be the first team in Finals history to come back from a 3–1 deficit and do it against arguably the best team of all time.”

2 — Expressive writing

Explicitly writing down your feelings and thoughts prior to a big game or event has been shown to decrease the amount of stress and anxiety experienced during the actual game and event.

Maybe the Houston Oilers in ‘93 should have written down some feelings at halftime before the Bills came back from 38 points to win the divisional playoff game in OT — known as “The Comeback”.

3 — Distraction techniques

Distraction techniques are focused specifically on reducing “explicit monitoring” and getting out of your own head. Here are 4 effective techniques:

Pre-performance routine (PPR)

PPR is creating a routine prior to the intended action. This can consist of things like certain movements, mental imagery, deep breathing, etc or a combination of these. This helps set up and prime the targeted movement without overthinking.

For example, Nomar Garciaparra doing an elaborate jig as he got into the batter’s box where he strapped and unstrapped his gloves and tapped his feet in the same sequence every single time (I can sense all the Yankees fans rolling their eyes right now).

Quiet Eye training

Vision is an extremely powerful tool (we’ve all heard “keep your eye on the ball”) but new research using eye-tracking technology has reinforced the extent of that power and value in movement performance.

Being able to focus on salient aspects of your goal — whether that’s a catcher’s mitt or rim or a certain part of the net — at the right time greatly improves your chances of success.

According to Joan Vickers, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Calgary:

“When your eyes provide the data, your motor system just knows what to do…your brain is like a GPS system. It detects target, speed, intensity, and distance.”

Training the eye to focus during this critical time frame has been termed “quiet eye training”. There is promising research linking it to improvements in basketball shooting, golf, marksmanship, and also surgery.

Left-hand contractions aka “hemisphere specific training”

In theory, using the left side of your body activates a part of the right side of the brain (a visuospatial process to be technical) that’s necessary for motor performance while suppressing the analytical processes of the left side of the brain linked to step by step internal cueing of skill execution.

In 5 different studies, researchers had players squeeze a softball in their left hand for 30 seconds prior to performing under pressure/stress. They found stable or increased performance in these players compared to players who did not squeeze the ball.

To all the Cowboys fans: yes, all Tony Romo had to do to not botch the field goal hold against the Seahawks was squeeze a damn ball before the play.

Dual tasking

Dual tasking is the act of performing a highly skilled movement while focusing on doing something else — like humming a tune or counting backwards. This takes the mind off the action and prevents internal step by step cueing. Dual-tasking has consistently been shown to increase performance in high-stress conditions.

Maybe all Nick Anderson needed to make those free throws was a little mental Macarena.

4 — Meditation

Mindfulness meditation continues to be linked to significant decreases in anxiety, panic, and stress. All are critical for performing under pressure.

A plethora of athletes have talked about using meditation to get an “edge”- ranging from Jeter to Lebron to Misty May Treanor and Kerri Walsh to Kobe to the Seahawks.

5 — Emotional regulation

Emotion-focused strategies can help with managing emotions and not allowing them to sabotage movement under high stress. Strategies include positive self-talk and social support.

6 — Stop thinking, just do it (I’m open to sponsors…)

From the same study I mentioned above about golfers, Susan Beilock found that experienced golfers put better when told to putt quickly rather than taking extra time.

If you’re a skilled expert, do it quickly without thinking. This prevents internal cueing from interfering with the automated process.

7 — Practicing under pressure

Practicing the movement or skill in higher pressure situations, like shooting a free throw with many people watching and taping instead of in an empty gym, has shown to improve performance under real-time high-pressure situations.

That’s why those IG and twitter videos of players making jumper after jumper in an empty gym don’t hold much weight.

Lastly, all these training activities further contribute to breaking the stress-failure cycle that often accompanies choking under pressure — when the athlete begins to associate high-stakes situations with failure. This creates a conditioned fear of failure and history repeats itself.

Breaking this stress-failure link by creating a new stress-success link can overwrite these previously learned associations, and thus break the cycle of choking.

V. The Takeaway

“It’s all just nerves” — true, but not in the way you may have thought.

Movement can change under pressure for a confluence of reasons. It takes a multi-factorial approach that considers the neuroscience along with personal characteristics to understand why movement “chokes” and how to guard against it or prevent it.

The next time you see a player struggling during a big moment, stop to think about what might be going on underneath the surface….in addition to being a “choking, good for nothing bum” of course.